The fall of the Egyptian pharaonic system, which had endured for over three millennia, is often attributed to a variety of factors: foreign invasions, internal strife, economic instability, environmental degradation, and a gradual erosion of centralized authority. These explanations, while grounded in evidence from dynastic records, archaeological strata, and classical accounts, fail in many respects to grasp the full metaphysical and cultural dimension of what the Pharaoh represented not merely as king, but as the incarnate axis of cosmic order, or Ma’at, on Earth.

This inquiry seeks to articulate the primary historical reasons for the fall of the pharaonic institution while simultaneously interrogating whether these reasons truly accounted for its dissolution or whether a deeper, perhaps misunderstood, dislocation of spiritual vision lay at the heart of Egypt’s decline.

I. Conventional Causes of Decline

1. Foreign Invasions and Dynastic Disruption

From the end of the New Kingdom (c. 1069 BCE) onward, Egypt increasingly succumbed to external pressures. The Libyans, Nubians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, and ultimately Romans all came to dominate Egypt, with varying degrees of cultural integration and imposition. The authority of the native Pharaoh was repeatedly eclipsed or usurped by foreign rulers who often adopted Egyptian titles and rituals without possessing the deep initiatic legitimacy understood by the priesthood and the people.

2. Economic and Environmental Strain

The Late Bronze Age collapse (c. 1200 BCE) sent shockwaves across the Near East. Trade networks disintegrated. The Nile’s inundation cycles became unpredictable, compromising agricultural abundance. Economic shortfalls undermined the vast bureaucratic and temple economies that had sustained the pharaonic state and its monumental projects.

3. Priesthood and Political Fragmentation

The growing power of the Amun priesthood, particularly during the Third Intermediate Period, challenged royal sovereignty. In some periods, the High Priest of Amun wielded more influence than the nominal king. This division of power, combined with civil wars between rival dynasties (e.g., the Twenty-first to Twenty-fifth Dynasties), eroded the integrative function of the Pharaoh as the unifier of the Two Lands.

II. The Question of Power: Misunderstanding the Role of the Pharaoh

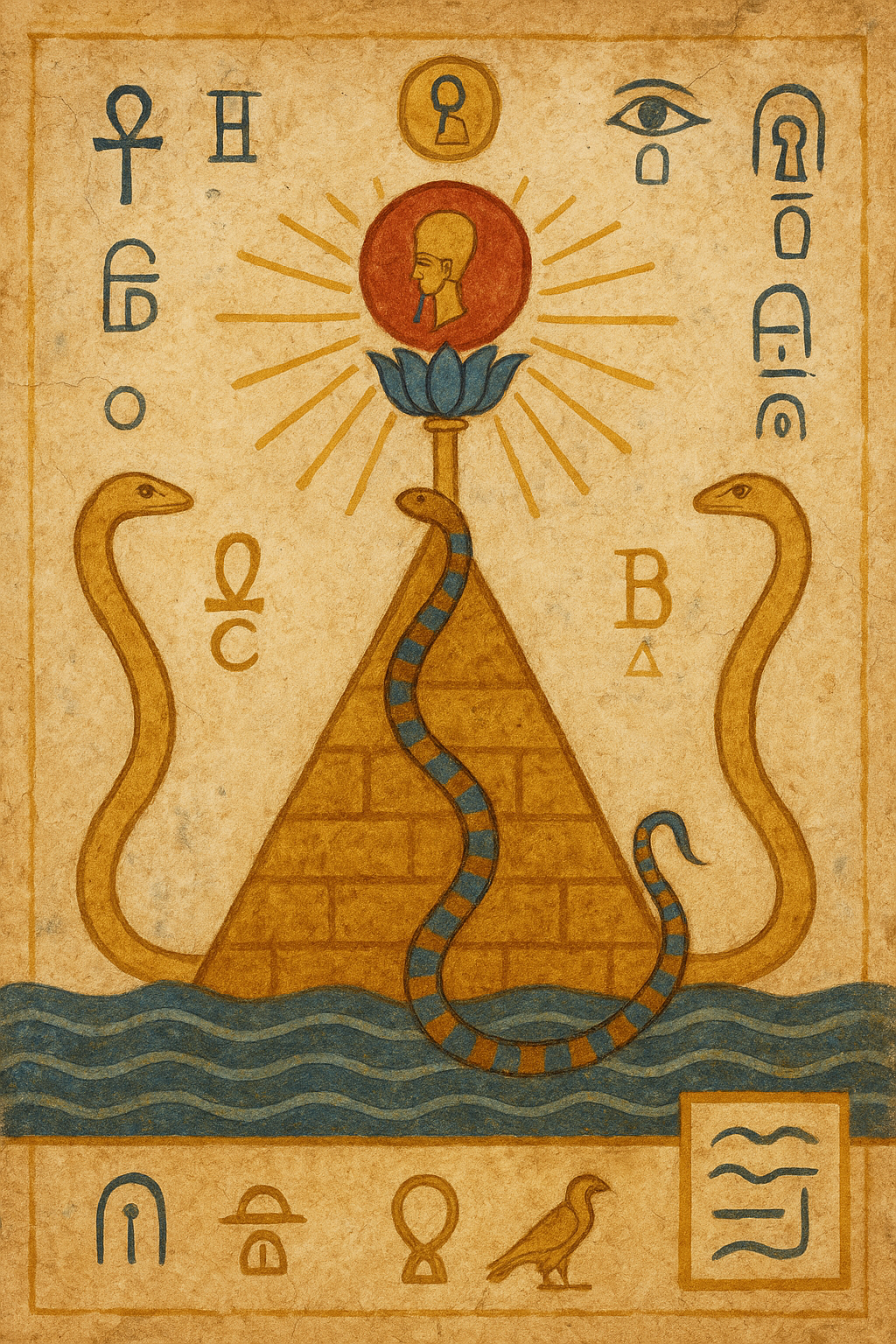

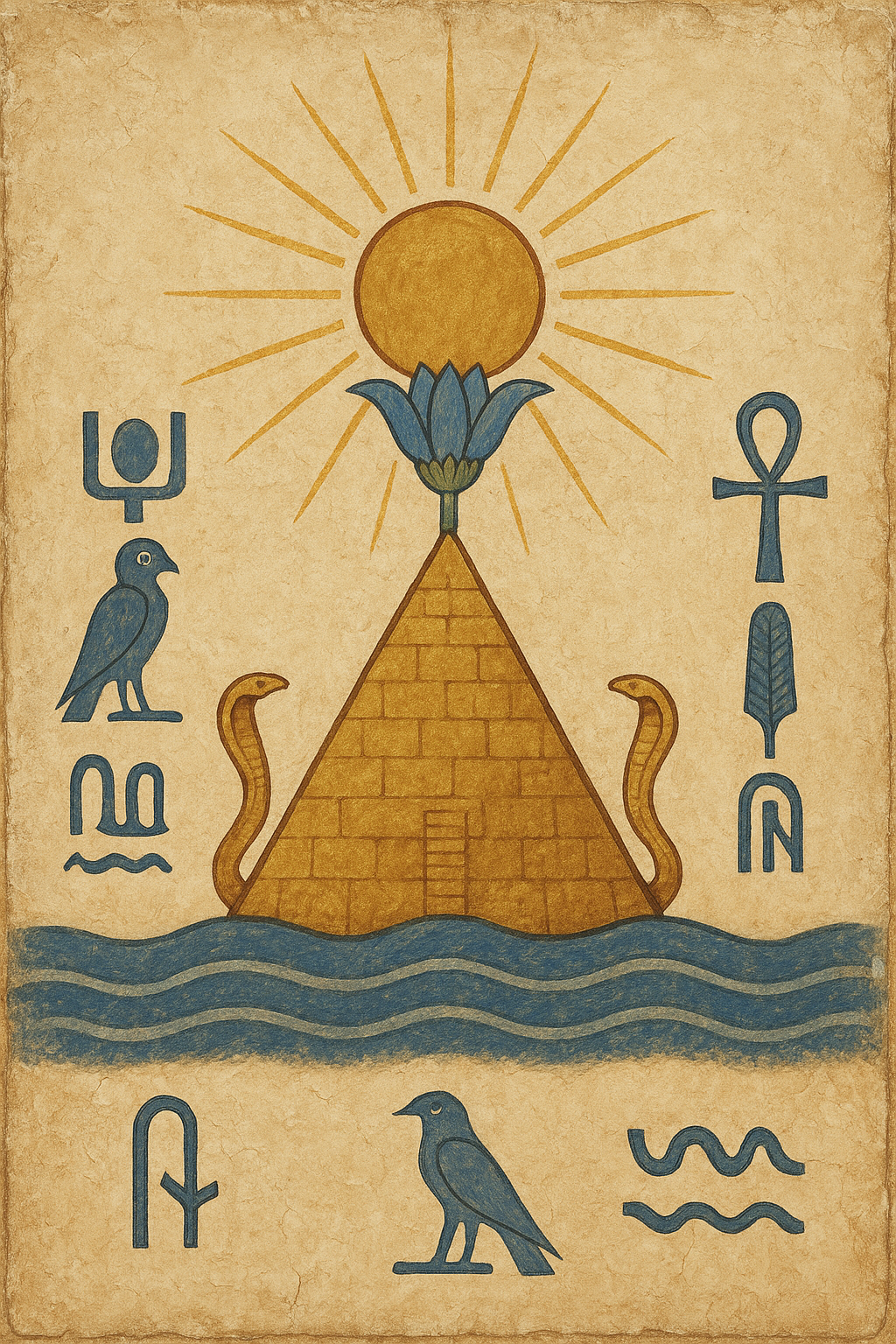

While the material and political factors outlined above are undoubtedly contributory, they present only a partial view. In the sacred worldview of ancient Egypt, the Pharaoh was not merely a temporal sovereign but the living vessel of divine authority, a reflection of Tehuti’s divine intelligence, Heru’s victorious light, and the upholder of Ma’at in both ritual and governance.

The decline of the Pharaohs cannot be fully understood apart from the loss of resonance with the deeper metaphysical order. Over time, especially during periods of foreign rule, the Pharaoh became a symbolic figurehead rather than an initiate of the Mystery Temples. This was no minor detail, for the true power of the Pharaoh rested not in military might or political strategy, but in heka (sacred utterance), sesh per ankh (divine wisdom writing), and the living alignment with cosmic order.

In this sense, it may be argued that the failure was not in the pharaonic institution per se, but in the failure of successive rulers and elites to truly embody the divine function they claimed. The rituals continued, the temples still functioned, but the flame of inner gnosis, the true priest-king path, had dimmed.

III. A Legacy Misunderstood

Modern historical narratives often regard the Pharaohs as autocrats whose power rested on divine propaganda. Such interpretations fail to appreciate the ancient Egyptian understanding of kingship as a sacred stewardship, a harmonization of the Ka of the land with the celestial order. To judge the Pharaohs by modern standards of power politics is to miss entirely the nature of their role.

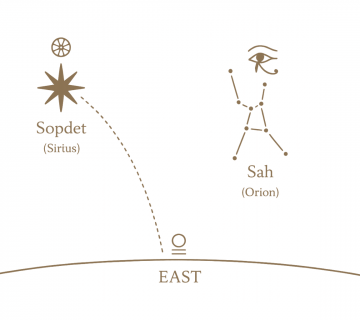

In truth, the decline of the Pharaohs may have been less about the failure of a ruling class and more about the gradual forgetting of sacred memory. As Egypt opened to foreign influence, as the temples closed and initiatory schools vanished, the luminous thread connecting the throne to the stars was severed.

Conclusion: Was the Decline Inevitable?

The demise of the Pharaohs was not merely the result of historical forces, but of an inward disintegration, a severance from the spiritual technologies and cosmological principles that had once animated the civilization of Kemet. The reasons commonly cited external invasion, economic hardship, political division were real but symptomatic.

The truer cause was a weakening of the sacred current: the gradual loss of the Pharaoh’s ability to act as a bridge between Heaven and Earth. The illusion that the Pharaoh was only a political actor contributed to his fall; when his sacred identity was no longer known, lived, or honored, the civilization he anchored unraveled.

In the end, it was not simply the Pharaohs who fell, it was a collective departure from the sacred science that had sustained Ma’at in the world. Their fall, then, is not just historical, it is initiatory. It speaks to what happens when humanity forgets the sacred center, and when power is divorced from the inner temple.